Special court orders cast doubt on Kevin Lane murder conviction

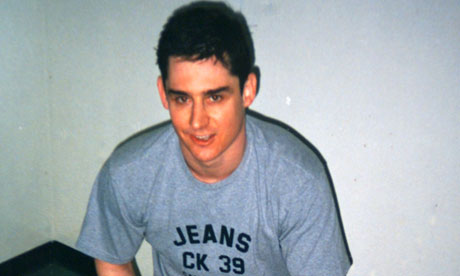

Kevin Lane has spent more than 18 years in prison, but has vowed to clear his name before being released

Kevin Lane says he is innocent of the crime for which he was convicted.

Photograph: Martin Argles for the Guardian

Doubts have emerged about the conviction of a contract killer following a trial in which special court orders were used to keep sensitive information out of the public domain.

Kevin Lane was convicted in 1996 of the murder in 1994 of Robert Magill, a car dealer from Hertfordshire. Lane's co-accused, Roger Vincent, was acquitted.

Lane, who has admitted to having been brought up in the criminal underworld, has protested his innocence since his conviction. Having served more than 18 years for murder, he is now in a category D prison – a sign that he is due for release soon. However, he has vowed to clear his name before his release and has launched a number of unsuccessful appeals that have raised questions about his conviction.

During his latest appeal hearing, last week, it was confirmed that many documents relating to Lane's conviction had been withheld from his defence team under public interest immunity certificates. The certificates, which are used to keep information from being disclosed in court, are often applied by judges to protect the identity of informants. But they also made it difficult for Lane to request documents that he believes could be instrumental in clearing his name. And documents that have been shared with Lane's lawyers have been heavily redacted.

It has emerged that some of the documents relate to a former police officer involved in the case, Detective Inspector Chris Spackman, who was instrumental in securing Lane's conviction but was jailed in 2003 for corruption relating to a separate case.

Prosecution lawyers involved in Lane's case and appeals have always maintained that Spackman's conviction, long after Lane was jailed, had no bearing on his case. However, during last week's hearing, it emerged that the police were aware of allegations that Spackman had been corrupt as far back as 1994, the year of Magill's murder.

It also emerged that among documents seized from Spackman's office upon his arrest was a reference to a file or files which were marked "Lane/Vincent". It is unclear why Spackman was in possession of the files.

The hearing was told that the commission had not seen or examined the files, and did not know whether the files were still available for examination. The material's existence was disclosed by the police to the Crown Prosecution Service.

Lane's barrister, Joel Bennathan QC, told the hearing that the fact that the police had such information but that it had never been made known to Lane's lawyers "ought to be a matter of the greatest concern".

It was alleged during the hearing that Spackman held "off the record" meetings with Vincent when he was in custody awaiting his murder trial.

Vincent, who was jailed for the murder of drug dealer Dave King in 2003, has always denied any collusion with Spackman, and any involvement in the Magill killing.

Spackman has also denied any suggestion of impropriety relating to the Lane conviction. Lane's lawyers will now review the information that has been shared with them.

About this article

Special court orders cast doubt on Kevin Lane murder conviction

This article appeared on p17 of the Main section section of the Observer on . It was published on guardian.co.uk at . It was last modified at .

This article appeared on p17 of the Main section section of the Observer on . It was published on guardian.co.uk at . It was last modified at .